Ideally, fashion is a site for meaning-making—through the outward-facing nature of clothing, individuals translate their inner self to an aesthetic exterior. Whether carefully curated or unintentionally formed, what one chooses to wear communicates the communities and identities they align themselves with. However, the blurred boundary between who people are and how they wish to be perceived is increasingly relevant in digital-age fashion choices. In a constant chase for self-representation, style highlights the dichotomy of conformity and authenticity in today’s society.

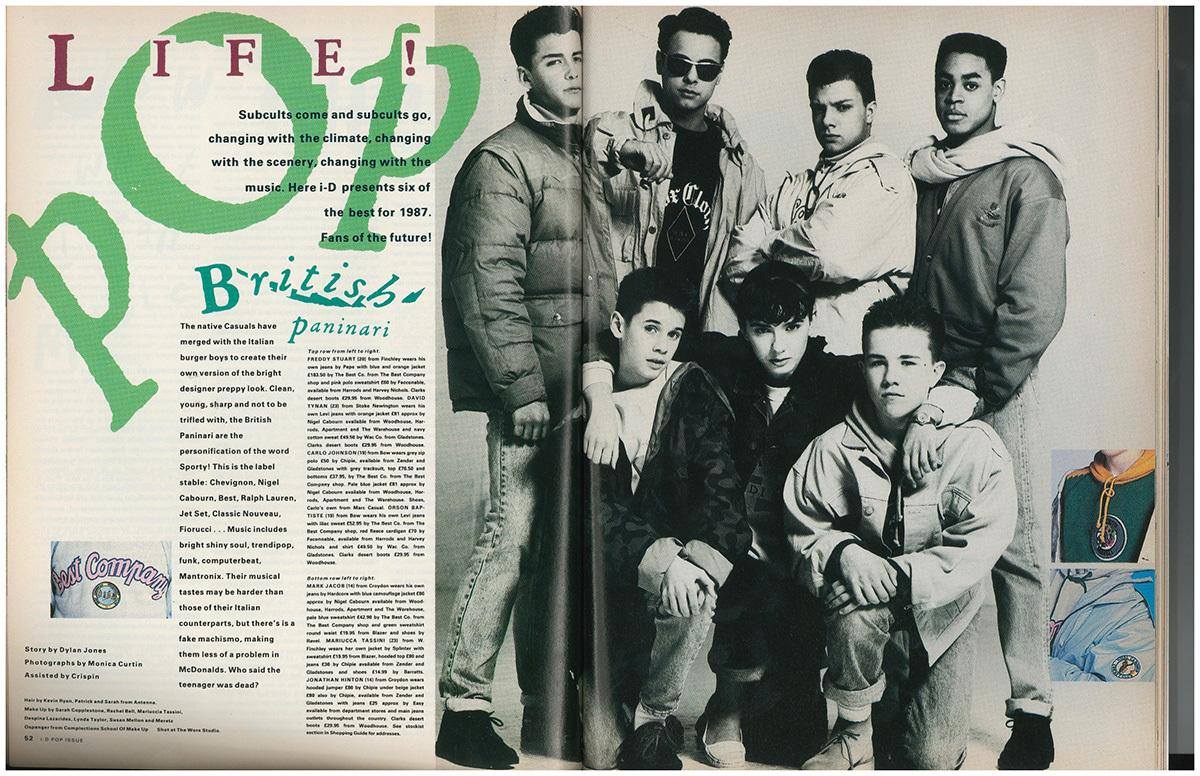

In some cases, belonging to certain social groups requires adherence to their fashion codes. Developed by the Chicago School in the 1920s, Subculture theory analyzed the growth of youth identity through shared reactions and interpretations of socio-political periods and cultural events. Subcultures were usually distinguishable through dress, as the styles of punk, goth, scene, and emo communities developed meaning through their association with the beliefs of their respective groups. The importance of fashion to subcultures made identity synonymous with appearance and illustrated fashion’s power to transcend the surface level. However, the advent of social media microtrends signals a departure from subcultures into the industrial complex of -core suffix aesthetics (cottage-core, gorp-core, ballet-core, etc.). Due to their fleeting, trend-based nature, -cores usually fail to communicate anything meaningful about the identity of the wearer. Instead, they exemplify how people can now jump from trend to trend, trying on whatever the algorithm is currently pushing.

The emergence of the “how to dress like ___” trend on TikTok encapsulates this newfound “playing dress up” philosophy of style. These audios dictate the process of dressing like a Lower East Sider or Copenhagen girlie and narrate how others, ostensibly outsiders, can also accomplish the look of possessing this identity. Those who follow along the audio’s instructions aren’t trying to replicate a lifestyle, but rather impersonate the look of someone they’re not. This is possible because new digital age aesthetics lack the exclusivity of subculture-era fashion—those who partook in a subculture’s style without initiation into the other aspects of the community were disparagingly labeled “posers”. Now, anyone can dress as whoever they want, regardless of membership in the associated community.

Part of fashion’s allure is being able to try on as many looks as you desire in a costume-like manner. With its unique power of subverting and redefining societal norms, clothing transcends the boundaries of gender, culture, and even class to an extent, ultimately allowing individuals to realize their ideal selves on their own terms. And in some ways, social media and fast fashion facilitate the growing customizability of style. The distinct look and feel of once-niche subcultures/aesthetics are co-opted by corporations and disseminated into mainstream consumer cycles. But with so many external influences and a plethora of options, realizing one’s identity in fashion form becomes increasingly difficult.

Ultimately, both the internally derived and externally manufactured facets of style are equally important in navigating the infinite choices that construct identity. It’s simply up to the individual to piece together authentic representation amid fragmented, consumption-motivated stimuli. Symbolic of the ever-nebulous negotiation between a person and the way they dress, we can come to understand style as a malleable and self-dedicated tool for both self-actualization and generating identity.

Reach writer Sarah Yu at musemediauw@gmail.com. Instagram @_sarahyu