Gaudy vs. Glamour

The world seems to come to a standstill when a celebrity wears something extravagant. Critics will criticize, fanatics will fawn, but at the end they all settle on the same conclusion – these celebrities, due to their status and their fame, will always know better than the average person, and therefore, are always glamorous and never gaudy.

As an uncommonly used word in the modern fashion aficionado’s vocabulary, gaudy has a negative connotation. The word essentially means extravagance— but not in the complimentary way you’d think. Gaudy refers to something so excessively extravagant, that it becomes completely and utterly tasteless. Compare that with one of its antonyms, glamour, and you start to realize the line that separates these definitions is an extremely opaque, thin string. It’s a word that most know the definition of: something so extravagant that it is the very essence of opulence.

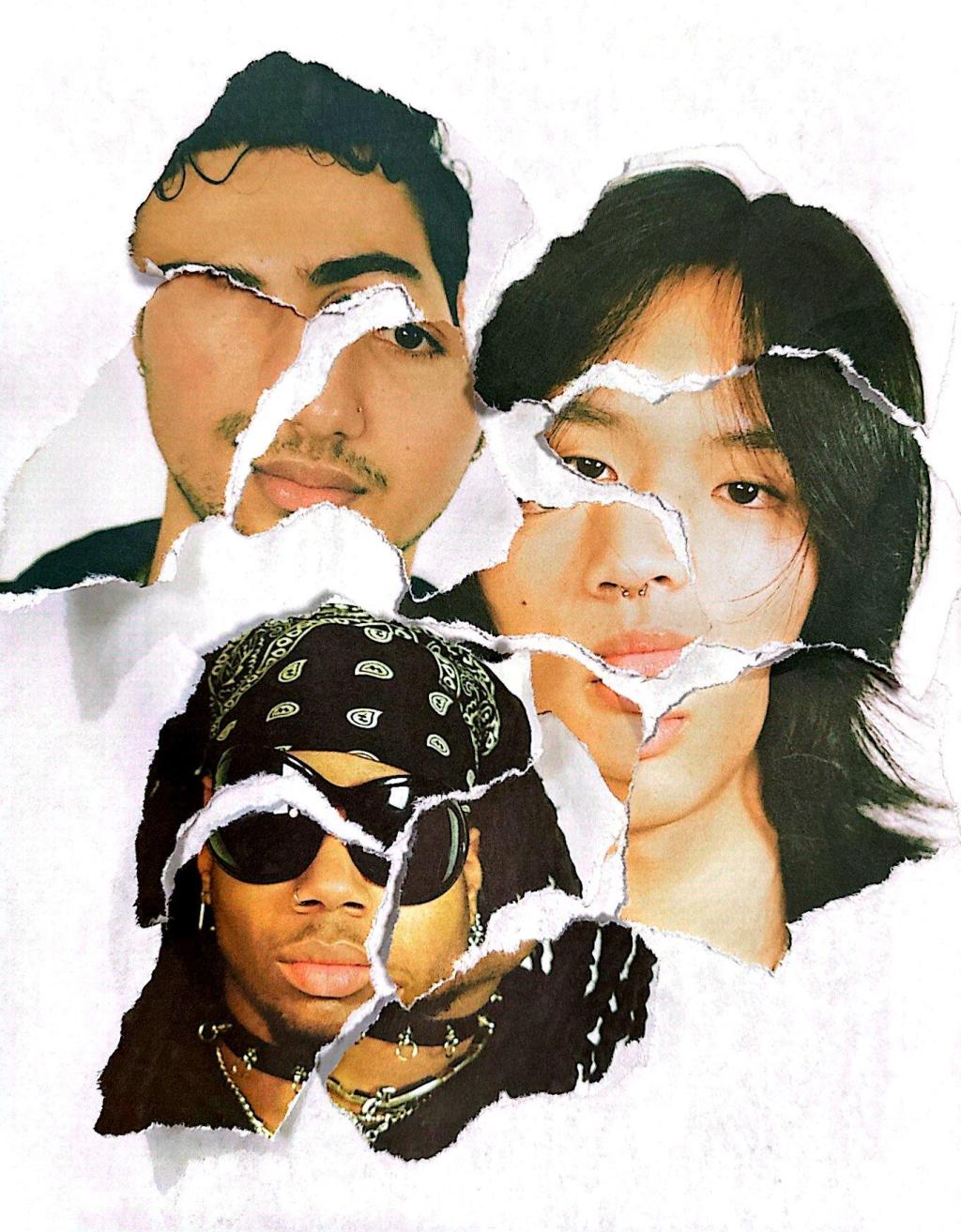

But what distinguishes these two words? Who decides whether certain accessory colorways or jean styles are gaudy instead of glamorous, and why? Many styles, subcultures, and ways of dress have long been denounced by the general public, for being too “showy,” “tacky,” or just plain embarrassing. Fast forward to today, and the same styles that were once scorned when worn by their originators are now celebrated on imitators, who selectively adopt elements that they favor, leaving behind the struggles inherent in “just an outfit” and presenting a “high class,” gentrified rendition of the original.

An example of this trans-socioeconomic adoption of subcultures is street style. Now seen on celebrities and modern day influential figures such as Hailey Bieber, this style characterized by oversized clothing, gold accessories, and an effortless vibe first appeared in New York City hip-hop culture in the 1970’s and 80’s, where Caribbean and African-American youth would come together in boroughs like the Bronx to celebrate music and community. As this style continued to grow and gain traction within the black community, it also began to borrow elements from LA chicano culture, and insert itself into the celebrity stratosphere as well through the rise of hip hop. As the turn of the millennium came, celebrities from these communities like Aaliyah, Jennifer Lopez, and Jay-Z could all be seen sporting the baggy clothing and unique accessories, inspiring youth of the time to emulate the style as well.

Along with this, however, came criticisms. The very minorities who pioneered streetwear were seen as “less dignified” when wearing it, as negative stereotypes associated with the style were perpetuated in the media. This was different for their white counterparts. Celebrities such as Justin Timberlake during his “NSYNC In Concert” tour and Taylor Swift in her “Shake It Off” music video have been seen donning the same, if not similar outfits, but have faced little to no criticism.

As 2020 rolled around, this style was once again taken by white celebrities and packaged as their own – under the name “Clean Girl Aesthetic.” The aesthetic, which made waves on social media at the height of quarantine, was led by the likes of Hailey Bieber, Sofia Richie Grainge, and other white influencers. Characterized by slicked-back hair, a glossy lip, gold hoops, and “effortless” (oversized) clothing, the style bore an uncanny resemblance to urban streetwear. The issue here was not that these celebrities enjoyed the style, but more that they presented it as their own brainchild, when the real pioneers had been looked down upon for doing the exact same thing.

In the onslaught of the so-called “2014 renaissance,” styles popularized by older Gen-Z are making a resurgence – with a twist. Indie sleaze, one of the defining styles of the era, is an amalgamation of grunge styles from the 90s combined with elements from the 70s and 80s. No one knows who truly kickstarted the trend, but many can agree that it first sprouted legs on the somewhat-forgotten social media platform Tumblr. Attitudes that were often paired with this style were reminiscent of what is widely considered to be “typical” teenage angst, hating authority, being unique, and making do with what you have. As the trend continued to pick up, it snowballed into something of an online subculture, becoming a kindred bubble for teenagers on the internet to share with each other their deepest thoughts and struggles. However, as celebrities embraced this trend, it devolved into a competition to conform to a predetermined image rather than an authentic expression of individuality. The diluted meaning of the dress became solely about appearance, devoid of the deeper significance it held for its original proponents.

Most fashion-inclined youth had little sense of what the term “camp” meant until the 2019 Met Gala, themed “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” inspired by Susan Sontag’s seminal essay “Notes on Camp.” As stars showed up on the red carpet, the theme of what camp meant slowly became more and more familiar, something we had seen before on celebrities such as Lady Gaga and Katy Perry, previously unrecognized and unlabeled. Fashion publications and critics lauded their audacious styling, as the ensembles worn to the Met Gala were considered in tandem with “sophisticated” and “high class.”

However, this hasn’t always been the case for the people who developed these styles from their personal creativity and experiences. To tell the truth, camp is something more complex than any one of us can truly comprehend. It’s a living, breathing entity of self-expression that presents itself differently to every single interpreter, but for the sake of keeping ideas linear, camp will be defined in line with the modern-day American pop culture definition. The style spans far back, in a time where scoffed-at and mocked queer people lived their lives bravely and honestly, decades before gay marriage was legalized in the US. Camp, with its roots in New York’s underground ballroom scene and queer black culture, emerged as a form of self-expression that defied societal norms. Members involved in the scene were encouraged to perform the ultimate acts of self expression through their clothing, dressing in ways that made them stand out in a given crowd. At this time, the general public was uninterested in a sense of identity through unique fashion, and dressing differently was met with much less envy than today. And as time passed, these views changed.

The 2010’s, like every other decade, had its defining styles, but more individuals were looking to purposefully stand out than ever before. This served the Met Gala with the perfect climate to take full advantage of previously booed garments and turn them into something “classy” all in the name of branding because a white cishet person was wearing them instead of a black queer one. This is not to attack those celebrities who have built their career off of these styles, such as Gaga and Perry, who have shown extensive love and support to the queer community that comprises much of their fanbase, but to criticize the higher up institutions that have historically shunned queer people yet stolen from their artwork. At the end of the day, the celebrities will always face better reception – regardless of who truly wore it best.

Despite all this, one can argue that fashion is art. It is meant to be influential and interpreted in one’s own way, built upon and tweaked over time by anyone – despite their race or socioeconomic class. Denial of this point is futile, but adding on to it is necessary. Yes, fashion is art, but it is always important to give credit to the ones who created it first. Similar to how one needs to obtain the rights to a song before sampling it, the standard for sharing all forms of art should circle back to crediting the creators. It’s impossible to control what one wears, but the double standard shown between what is deemed gaudy and what is deemed glamorous is off-putting at best and jarring at worst, and identities among oppressed groups can become warped with senses of low self-worth instead of pride. This problem cannot be solved with pinpointed blame on an individual or a group, but rather our society, the culture we have created that uplifts higher class, generally white celebrities for doing the same gaudy things we all do. We as consumers need to learn to recognize art in its own right. After all, fashion isn’t good because someone rich and famous wore it – it’s glamorous because it can stand on its own.

Reach column writer Preethi Makineni at musemediauw@gmail.com

Twitter or instagram @pr3eth1