Carol Christian Poell’s Spring/Summer 2004 show was set in the Naviglio Grande canal. Well-dressed models floated down the canal on their backs, their faces pale and bodies still. This macabre imagery, coupled with the show’s title, “Mainstream-Downstream,” and the overt reference to Millais’s Ophelia, bluntly formed an analogy for how popular fashion was killing the craft of making clothes.

I liked this simple, conspicuous metaphor, and I think Poell did, too. Convoluted, fanciful allegories are for starry-eyed artists, and Poell rejects the identity of “artist” in favor of “artisan.” To him, artists are dubious characters whose motives couch behind pretense and canting. The artist leverages their trade for social, political, or moral designs. They aim to coax a person towards action, indict a perceived injustice, or peddle a belief. The artist’s techniques are always the means, never the end. Their goal is one that transcends, distorts, and ultimately betrays their craft.

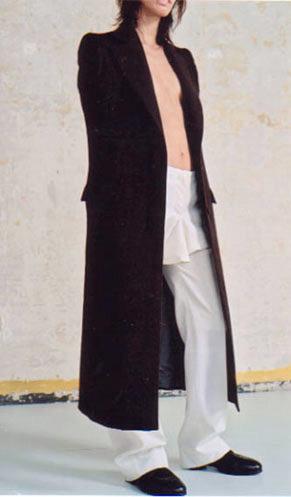

On the other hand, the artisan dedicates themselves entirely to this craft. Among the artisans in fashion, Poell may be the most genuine. More than anyone else, he is consumed by the process of making clothes. He wanted the garments he made to be so pure and self-evident that they would dominate and “annul” the wearer’s body. Sometimes Poell delivered the theme of annulment very literally, either by hiding the identifying features of his models or by designing clothes that physically restrained them. He also explored this idea indirectly by sourcing exotic materials or using bizarre techniques to create clothes with inherent character that would overpower that of the wearer. Examples include ties made from human hair, leather jackets with dye injected through the animal’s veins, and boots with rubber drippings reminiscent of blood.

However innovative his techniques, Poell does not flirt with the absurd. His clothes are always sincere. He never designs garments so abstract, reinventive, or unconventional that they would be better categorized as sculptures. A jacket appears as a jacket, a shirt as a shirt—this unique conservatism chafes against mainstream fashion. Many designers and consumers would much rather create and purchase symbols than clothes. Whether it be nostalgia, status, or their beliefs, they expect clothing to express something more than the sum of its parts. Preoccupied with what garments represent, they often disregard how they are constructed.

There will always be a place in fashion for expressing personal values and driving social change, but a designer as refreshing as Poell comes along so rarely. No one else is as engrossed with how clothes are made. No one else holes up in their atelier for months to stitch titanium insertions between the lining of jackets or to manually construct zippers, one tooth at a time. No one else experiments as extensively with novel techniques like object-dyeing, tanning leather to transparency, and weaving glass into fabric. Many designers have succeeded by pushing outside the boundaries of making clothes, but no one besides Poell has accomplished so much by staying within them. The beauty, drama, and triumph of his work is not borrowed from “nobler” ideas like individuality, freedom, or justice; rather, it comes from the simple acts of cutting, dyeing, and sewing.

Reach column writer Alan Zeng at musemediauw@gmail.com

Instagram @alanz.eng